The Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos) is one of the world’s largest, most powerful, and widely distributed birds of prey. They have been revered as sacred messengers and upheld as symbols of imperial power and statehood in cultures around the planet, inspiring awe, acclaim, reverence, and sometimes fear. Slightly smaller than a Bald Eagle on average, the Golden Eagle surpasses the Bald Eagle in weight, speed, and wingspan. They can be remarkably elusive for such large birds, but a sharp-eyed observer might spot wintering eagles on the blufftops and steeply wooded coulees of the Driftless area. Look for a large, regal eagle with chocolate brown plumage, feathered or ‘booted’ legs, a lustrous golden nape, and massive feet.

Length: 2.3 to 2.7 feet

(70 to 84 centimeters) from beak to tail

Weight: 6.6 to 13.5 pounds

(3 to 6.125 kilograms)

Wingspan: 6.06 to 7.3 feet

(1.85 to 2.2 meters)

Top Speed:

Close to 200 miles per hour

Longevity:

The oldest recorded Golden Eagle was at least 31 years, 8 months old, when it was found in 2012 in Utah. It was banded in Utah in 1980.

Diet

Golden Eagles feed on a wide range of prey, focusing on whatever mammals and birds are locally available. A breeding pair on the steep slopes of

Bathurst inlet in Nunavit might take seals, arctic fox, marmots, arctic and snowshoe hares, ermine, wolverines, ptarmigan, a wide variety of waterfowl, and whale and dolphin carcasses that wash ashore. In the Driftless, that same pair will feed on wild turkeys, pheasants, weasels, cottontail rabbits, red and grey fox, coyote, white-tailed deer, and roadkill and farm carcasses. While Golden Eagles are renowned for their large, impressive kills, they most commonly eat medium-sized prey like rabbits and ground squirrels.

The Raptor Resource Project Golden Eagle Tracking Project

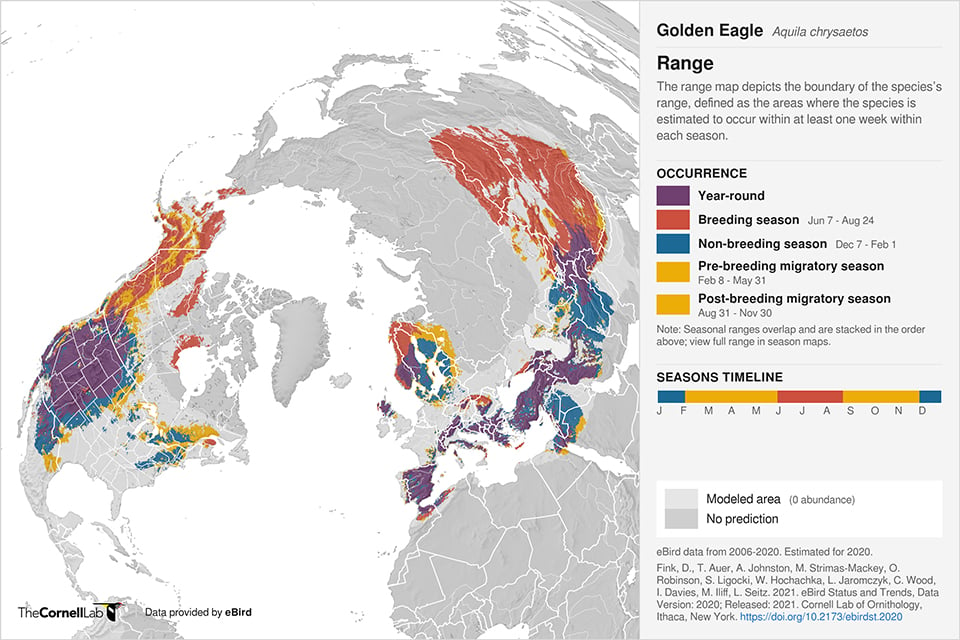

Golden Eagle range map generated by eBird.org

In North America, Golden Eagles breed in most of Canada, Alaska, the western half of the United States, and northern and western Mexico. Most eagles that nest in northern Canada and interior and northern Alaska migrate thousands of kilometers to their wintering grounds, which includes the Driftless area of Iowa, Wisconsin, and Minnesota.

The Raptor Resource Project began a Golden Eagle research study in January of 2022. We are monitoring wintering Golden Eagles in the Driftless Area to learn more about their movement on their winter and summer range with potential nest locations, seasonal migration patterns and timing, and route fidelity. Research is being conducted under the guidance and permits of RRP’s Jeff Worrell, former director of the National Eagle Center, and raptor biologist Brett Mandernack. We hope our study helps answer these questions and makes people, especially in the Driftless area, more aware of their wild neighbors all year long.

We need more eyes in the sky for our Driftless Golden Eagle program. If you see Golden Eagles, or believe you have them on your land in the Driftless area of Wisconsin, Minnesota, or Iowa, please contact Amy Ries at [email protected], or text 621-237-5793. We would love to learn more!

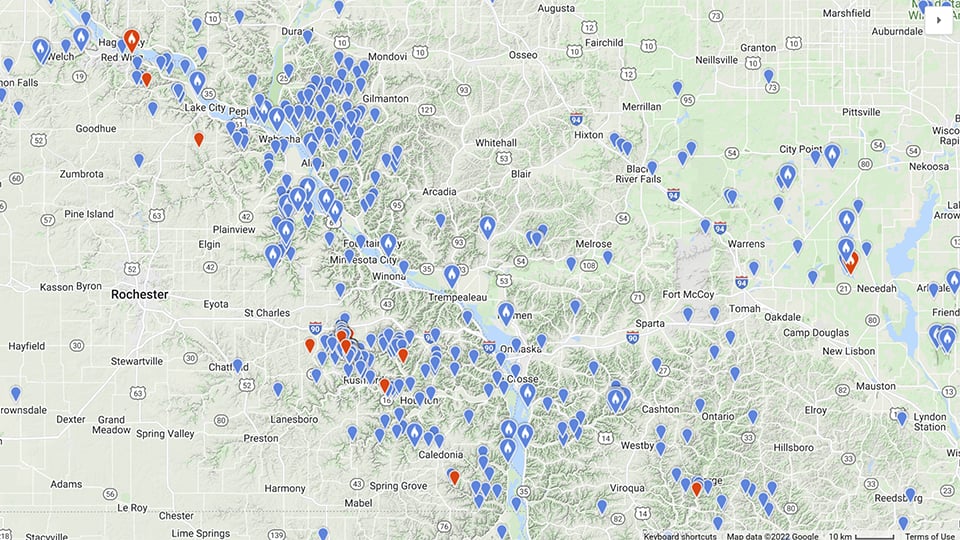

Golden Eagles reported in the Driftless between December and March, 2012 to 2022. Map generated by eBird.org

Canny Hunters

A hungry Golden Eagle cruises the Driftless in a low soar, hugging the steep upslopes and rising high over the valleys that roll beneath her. She spots a red fox crossing an open field and drops behind a bluff, using the terrain to conceal her approach. The wary fox won’t see her until it is too late to escape.

Golden Eagles tailor their hunting techniques to suit the terrain, conditions, and prey they are hunting: diving from a high soar, quietly ambushing from a low perch, walking up to and seizing prey on the ground, or soaring low over hills and valleys to conceal their approach. They aren’t social animals, but small groups have been documented hunting cooperatively and mated pairs sometimes engage in tandem hunts.

Her mate joins her and the two rise swiftly over the ridge. He folds his wings to stoop at the running fox, while she glides in low and fast for the kill. The fox is concentrating on her mate and doesn’t see her coming up behind him.

Deadly, Formidable Feet

He hurtles downward with surprising speed for such a large bird. She glides in behind the fox, who is swerving to avoid her mate. She brings her feet forward, spreads her talons, and strikes. Success! She grips the fox firmly with her large powerful feet, subdues it, and begins to eat.

A Golden Eagle’s footpad measures 5.1 to 5.7 inches long. It is tipped with four formidable talons that are about two inches long, giving it a greater reach than the human hand. Golden Eagles need feet that can grasp a wide variety of prey in the harsh environments they call home: researchers have witnessed them attacking and killing antelope, deer, sheep, seals, mountain goats, coyotes, badgers, bobcats, turkeys, geese, cranes, herons, hares, marmots, and ground squirrels. They kill with their feet: as Leslie Brown states “[A Golden Eagle’s] feet can accommodate themselves to the size and shape of the prey taken, a small animal being crushed in the grip of the overlapping talons; while a wide spread of the foot, enabling the bird to seize a large animal, also places the talon points in a position to pierce…”. Golden Eagles often live in cold places and feathered or ‘booted’ feet – a trait shared by just two other diurnal raptor species – protect them against the cold and bites or scratches from their prey. Once a Golden Eagle has dinner in its grasp, it grips and crushes with its large, powerful feet, using its sharp, hooked beak to tear flesh from bone.

Incredible Flyers

As if a Golden Eagle’s massive feet, adaptability, hardiness, and intelligence weren’t enough, the species is remarkably fast for such a large bird. Leslie Brown estimates that a Golden Eagle can achieve 180 miles an hour in a vertical dive, while Brown and Amadon put their speed at between 150 and 198 miles per hour. We’ve seen them making roller coaster or undulating flights high above coulees: rising high into the air, rolling over on their backs, falling rapidly, and effortlessly rising to do the same thing over again. Depending on the situation, a Golden Eagle might be displaying antagonistically (this is my territory!) or impressing a mate (watch me fly!).

A Bond Across Years and Miles

Their hunger sated, the wintering pair seeks a favorite roost in the lee of GrandDad rock, a massive chunk of grey limestone that overlooks the steep, narrow valley. Noise travels for miles in the bitter cold: a chainsaw, a train, a barking dog. Soon the two will return to their breeding grounds, trading the sights and sounds of the Driftless for the shores of Hudson’s Bay or the rocky slopes of Bathurst Inlet in Nunavit: one of the most isolated and sparsely settled regions in the world. We’ll look for them here next winter and track them via satellite while we wait.

Territorial displays, mutual soaring and gliding, mutual aerial displays, vocalizing, chasing, long periods of perching close together, foot touching, flying along cliffs, nest building, footing, nibbling, body brushing, food sharing, and copulation all reinforce a couple’s bond on and off their breeding territory. Golden Eagles are a long-lived species and couples stay together across tens of years and thousands of miles. Their intelligence, speed, strength, and strong pair bond help them raise young in one of the world’s most rugged and remote places.

Once they return home, she will lay one to three pale eggs lightly blotched with brown. Both eagles will incubate, brood, and feed young, although she will provide more direct care and he will provide more food. Their young will fledge 65 to 70 days after hatching – just in time to take advantage of the brief but intense northern summer before winter sets in and the eagles migrate back to their wintering grounds on the Driftless.

Catching eagles can be frustrating. Golden Eagles don’t care that it’s -25F; steep, icy slopes are hard to navigate in the dark, and fingers don’t work well in the bitter cold. A frenetic burst of work is usually followed by hours and hours of watching and waiting for something to happen. But as I admired (and sometimes cursed) the Golden Eagles high up on their rocky perch, I came to a true appreciation of this amazing species: a species that lives and thrives in conditions that would quickly kill my fragile human self. We look forward to learning more about them. If you would like to donate to our Golden Eagle project, please follow this link.

The Raptor Resource Project

The Raptor Resource Project The Raptor Resource Project

The Raptor Resource Project