Do bald eagles go through menopause? Probably not, since we’ve documented menopause or prolonged post-reproductive lifespans in just four species. The question came up when Elfruler and Donna Young got Ma FSV’s band number and discovered she was 22 years old – a marvelous matriarch who likely began breeding at Fort St. Vrain back in 2007. Keep reading to learn more!

Eagles and Ova

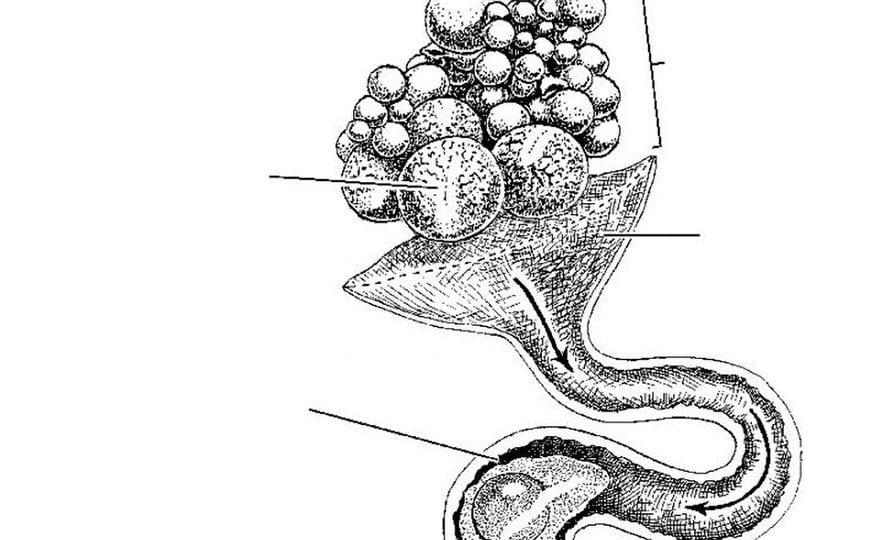

Ova and fallopian tubes, Avian Reproductive System, Handbook of Bird Biology

Ova and fallopian tubes, Avian Reproductive System, Handbook of Bird Biology

Like mammals, birds hatch with a fixed number of ova in their ovaries: an amount that varies between species, families, and genera. We know that breeding female bald eagles generally release between one and four ova every year, but to know how likely they were to go through menopause, we’d have to know how many ova they have. Members of Spizaetus, a genus of tropical eagles, appear to have between 54 and 60 based on egg-production records and post-mortem examination of breeding adults. But sea eagles aren’t all that closely related and we don’t know whether this applies to them as well.

How many eggs have our eagles laid?

We have reproduction and age records from three bald eagle nests: Decorah, Decorah North, and Fort St. Vrain. What do they tell us about bald eagle age, fertility, and marvelous eagle matriarchs?

- Decorah Eagles: In 2024, Mom turned twenty-two years old. That we know, she has laid 39 eggs so far: two in 2008 and three egg every year since 2009, with one failing to hatch (2016), one breaking (2019), and two years we don’t have data on (2022 and 2023). If she keeps laying three eggs per year, she has five years to go before she reaches 56 eggs. There are very few studies of free-living birds over the course of their entire reproductive lives. This underscores the importance of keeping records. Counting offspring and years helps answer questions about how long females can breed and how many ova they have.

- Decorah North Eagles: We don’t know how old DNF is, but we don’t think she has been breeding very long. Assuming that 2019 marked her first year, she has laid eleven eggs to date.

- Xcel Fort St. Vrain Eagles: Ma FSV, aka 0629-44094, is twenty-two years old and we think she began nesting in 2007. In 2006, the first egg at FSV was laid on February 17. But in 2007, the first egg date was pushed back March 3. Over the next few years, the first egg arrived earlier and earlier until Ma was laying around February 16 every year: a pattern we also see at peregrine falcon nests. If we are right, Ma FSV has laid 39 eggs since she began breeding in 2007. Like Mom, she has about five years to go before she reaches 56 eggs. Thanks to Donna and Elfruler for getting Ma’s and Pa’s band number!

Mrs. North, the first female eagle at the North nest, had a very unpredictable egg clock! We only watched her for three years, but during that time, her earliest egg arrived on February 19, 2017 and her latest arrived on March 11, 2016: almost a month later. I didn’t include her data because we don’t know how old she was, how many eggs she had laid over the course of her lifetime, how long she and Mr. North had been breeding, or when Mr. North arrived.

New mates and reproductive changes

Why do new mates push lay dates back? In some cases, mate succession happens when one bird pushes another off territory early in the breeding season. If the interloper is female, the resident male will need to bring her into condition for eggs. If the interloper is male, he’ll need to bring the resident female into receptivity. But even when that doesn’t happen – for example, Pa Jr. began hanging out at Xcel Fort St. Vrain in the fall of 2020 – the egg-laying schedule frequently shifts earlier, especially for the first couple of years.

- In 2009, her second year on site, Mom Decorah laid egg #1 on March 2. She advanced to February 25 in 2010, to February 23rd in 2011, and to February 17 – her earliest date! – in 2012.

- In 2019 and 2020, DNF (Decorah North) laid her first egg on February 21. She laid egg #1 on February 15 this year – the earliest she has ever laid an egg.

- In 2007, Ma FSV laid egg #1 on March 3. She advanced to February 28 in 2008, February 27 in 2009, and February 17 in 2010. When Pa Jr. replaced OP in 2021, her egg-laying shifted back to early March.

Menopause: Very Uncommon

Menopause is rare in the animal kingdom. In mammals, menopause occurs one year after an individual’s final natural ovulation cycle and is marked by changes in hormone levels and infertility. We’ve documented menopause or prolonged post-reproductive lifespans in just four species: human beings, orca whales, short-finned pilot whales, and the Ngogo chimpanzee group in Uganda.

These four species are all social, live in family groups, have long childhoods and lives, and practice intergenerational care. However it evolved – and there is a fair amount of argument about that, especially since elephants, another other long-lived social species, don’t go through menopause – it benefits this kind of group as a whole to have more members tending young, especially since they have long childhoods. Infants and toddlers are adorable, but not very good at caring for themselves.

So why doesn’t it make sense for all female members of these species to keep having children throughout their long lives? Social groups are pretty good at surviving: far better than individuals as a whole. Picture a group that’s guided by intergenerational knowledge, diverse skills, and members that share with and protect one another. They are fantastic at survival: at finding food, defending territory, and keeping their young safe. If every female in the group bears offspring every few years, the group will soon overrun the landscape and conflict will arise, threatening everyone’s survival. In a world of limitless resources, it might make sense for individuals in a social group to keep producing children throughout their long lives. But we don’t live in a world of limitless resources. I can’t answer the question of why menopause evolved, but I understand how it benefits us.

Can eagles (or falcons) undergo menopause?

An individual wild eagle or falcon might be capable of outliving its large supply of eggs, but neither are likely to experience prolonged post-reproductive lifespans. Falcons aren’t social and eagles are situationally social: they can be social under certain conditions, but don’t have systems of intergenerational care. Age and living take their toll: joints silt up, eyesight gets wonky, strength diminishes, and injuries inhibit activity. If a female belonging to a non-social species reaches menopause – and that’s not very likely given how long she would have to have lived – she will have a hard time caring for herself: finding food, defending a home or territory, remaining healthy, and not becoming prey. Prolonged post-reproductive lifespans might be less a matter of apoptosis and more about living in a group that tends to your basic needs.

Did you know?

- The oldest known wild bird in the world is Wisdom, an Albatross on Midway Atoll. She is at least 73 years old and was observed courting with a new mate, although it happened late enough that she probably won’t lay an egg this year. Will she every lay again? I hope we find out! https://friendsofmidway.org/wisdom-a-laysan-albatross-at-least-73-years-old-is-back-on-midway-working-the-dating-scene/.

- The oldest known wild bald eagle was 38 years old when it was struck by a car and killed. Adult male temperate zone eagles can produce fertile semen until the end of their lives.

- Waha Thuweeka (a.k.a. Bill Voelker), director of the Sia breeding project, told us that Golden Eagle Micah was 52 years of age when she laid the egg that produced her daughter Waipi. He wrote: “2020 was our fiftieth year of conducting culturally-based field observations of Golden Eagle populations that occur in the corridor of our historic Numunuh (Comanche) migration route used when our People left the high country of the Rockies and worked their way onto the Southern Plains. During the course of the past 50 years we have identified and verified, through unique plumage or anatomical idiosyncratic features, several individuals in the wild that have bred successfully in the same territories in excess of twenty-eight years!”. Having said that, I don’t know how many eggs she laid throughout her life or how old she was when she began laying them.

Things that helped me learn and write about this topic

- Jim Grier and Waha Thuweeka, aka Bill Voelker. Both men were an invaluable source of information and help.

- Nesting records. Nest cams are an excellent, non-invasive way to get accurate, long-range records of egg-laying, egg hatching, and fledge. With all we know, there is so much left to learn!

The Raptor Resource Project

The Raptor Resource Project The Raptor Resource Project

The Raptor Resource Project