We wrote this blog a year ago. I wanted to revisit it given the events at the North nest this year. Mr. North and DNF have been dealing with intruders for a couple of weeks. Instead of perching near the nest, packing in food, and developing the reserves she needs to lay eggs, DNF is guarding her nest, egg, and mate from potential rivals. After egg number one, her testosterone and progesterone should rapidly decrease, while prolactin, a hormone that induces incubation and brood patch swelling, should rapidly increase. Intruder-related stress might be keeping her testosterone and progesterone levels high and/or inhibiting prolactin, which could reduce incubatory behavior.

Will DNF lay another egg? It’s hard to say, especially since we have no idea where her hormonal regime is right now. I hope she doesn’t, since the difference in age and development would make things very tough for the youngest eaglet. But it’s all up to the eagles. Thanks for understanding and watching with us.

I loved watching Mr. North incubate eggs through today’s snowy weather. He turned his head out of the wind, closed his eyes to protect them from the blowing snow, and fell asleep as the nest rocked gently back and forth. What makes normally active birds like hawks, falcons, and eagles spend so much time sitting on eggs?

Hormones, egg production, and broodiness

As daylight length increases, birds’ gonads swell. Both sexes produce testosterone, although male birds produce more than female birds. Testosterone is associated with aggression, territoriality, courtship, nest-building, testicular development, and sperm production. Female birds also produce progesterone, aka the “pregnancy hormone”, which induces egg production. Most birds are louder and brighter in early spring, when bird song, plumage, and courting behavior are in full swing.

So why do eagles get ‘broody’ after they start laying eggs? Another hormonal change! After egg number one, testosterone and progesterone rapidly decrease, while prolactin, a hormone that induces incubation and brood patch swelling, rapidly increases. Opioid peptides help stimulate prolactin production. Perhaps a sudden, sharp rise in opioid peptides helps normally active birds switch from moving around to sitting on eggs all day.

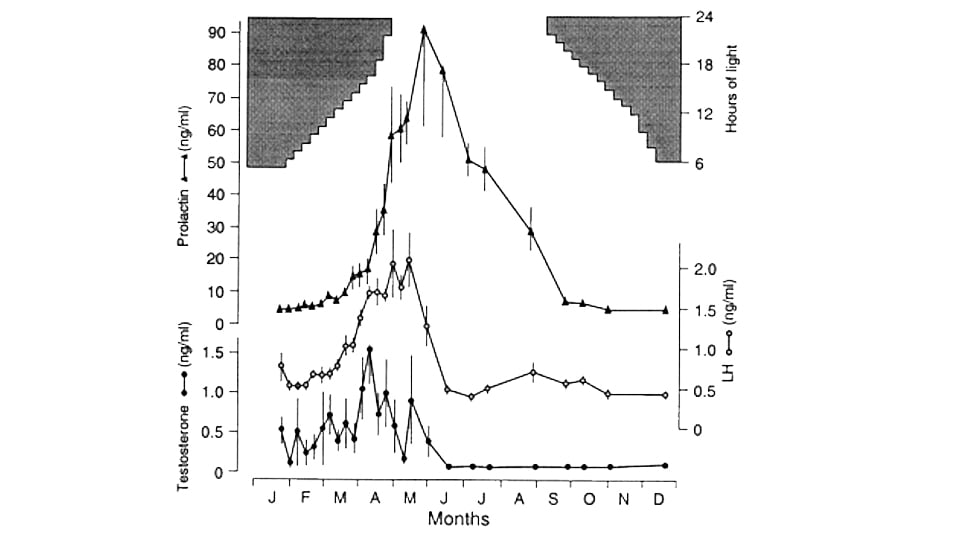

The chart below shows the relationship between daylight length, testosterone production, prolactin, and luteinizing hormone in male Svalbard Ptarmigans. Male Svalbard Ptarmigans don’t care for their young, but similar hormonal progressions have been observed in male birds that do. Testosterone peaks early, prolactin ramps up as testosterone falls, and prolactin production decreases rapidly after peak.

Changes in the concentrations of plasma testosterone, LH and prolactin in five captive, male Svalbard Ptarmigan exposed to seasonal changes in daylength

I couldn’t find a similar chart for Bald Eagles, but I suspect that peak prolactin probably lasts 45-50 days. Why? Eggs hatch 35 to 37 days after laying and eaglets need intensive care for their first ten to fifteen days of life. We’ll see both parents become more active as prolactin ebbs and metabolisms speed up – just in time to meet the demands of keeping two or three hungry eaglets fed. We’ll write more about that in 50 days or so.

Sweet Eagle Dreams, everybody!

References

- Peter J. Sharp, Alistair Dawson, Robert W. Lea, Control of luteinizing hormone and prolactin secretion in birds, Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0742841398000164#BIB72

- I.A Malecki, G.B Martin, P.J O’Malley, G.T Meyer, R.T Talbot, P.J Sharp, Endocrine and testicular changes in a short-day seasonally breeding bird, the emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae), in southwestern Australia, Animal Reproduction Science: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0378432098001109

- Raptor Resource Project founder Bob Anderson

- Uncovering the Sex-Specific Endocrine Responses to Reproduction and Parental Care: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fendo.2021.631384/full.

- How Can They Sit Still For So Long? https://www.birdsoutsidemywindow.org/2013/04/05/how-can-they-sit-for-so-long/

The Raptor Resource Project

The Raptor Resource Project The Raptor Resource Project

The Raptor Resource Project