Mr. North incubates his egg while raindrops bead on his feathers and roll down his back. Fortunately, he has about 7,000 feathers to protect him from the weather.

Different sources provide different answers about how many things birds do with their feathers, but all of them agree that insulation is important. The rain beading on Mr. North’s back shows us that feathers are insulative and water-resistant: the rain beads up on Mr. North’s back, but doesn’t reach his skin.

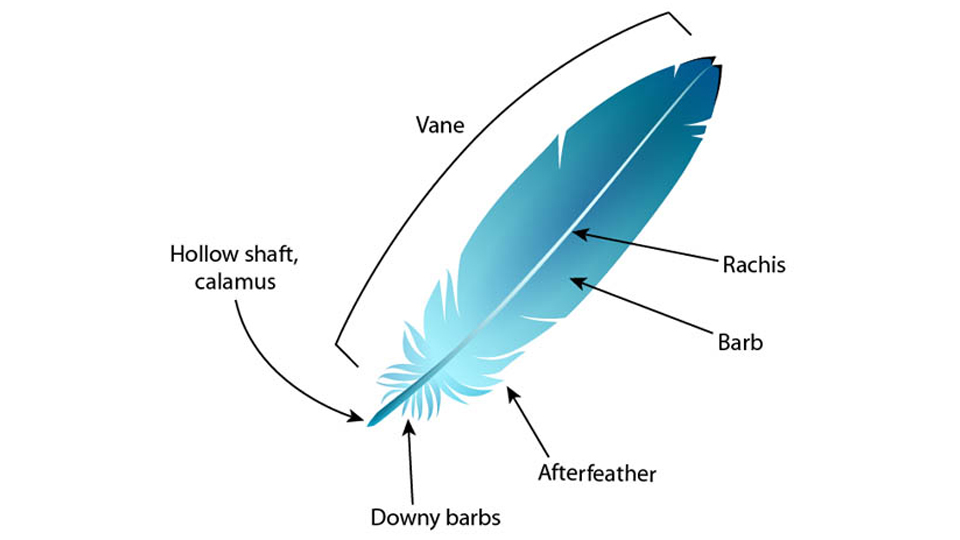

Feather Anatomy

Parts of a feather. Image courtesy Ask a Biologist.

There are two basic types of feather on an adult eagle’s body. Stiff exterior contour feathers zip together over fluffy down feathers: an overcoat that sheds water and keeps heat from escaping. Down feathers trap layers of air next to the eagle’s skin, where it warms quickly. An eagle can change how much air is trapped by moving its feathers to create more or less air space. I think of it as dressing in layers: the vane feathers form an ‘overcoat’ underlain by the soft, insulative down feathers.

How else do birds use their feathers? Feathers help birds fly, keep warm, control body temperature, provide weather protection, aid in swimming, diving, and floating (waterbirds and piscivorous birds), snowshoeing (ruffed grouse), sliding (penguins), balancing, feeling, hearing (owls, harpy eagles, northern harriers), making sounds, muffling sounds (owls), foraging, keeping clean, constructing nests, transporting water, escaping from predators, sending visual signals, and camouflage. Since feathers do so many things, it isn’t surprising that they come in more than one shape.

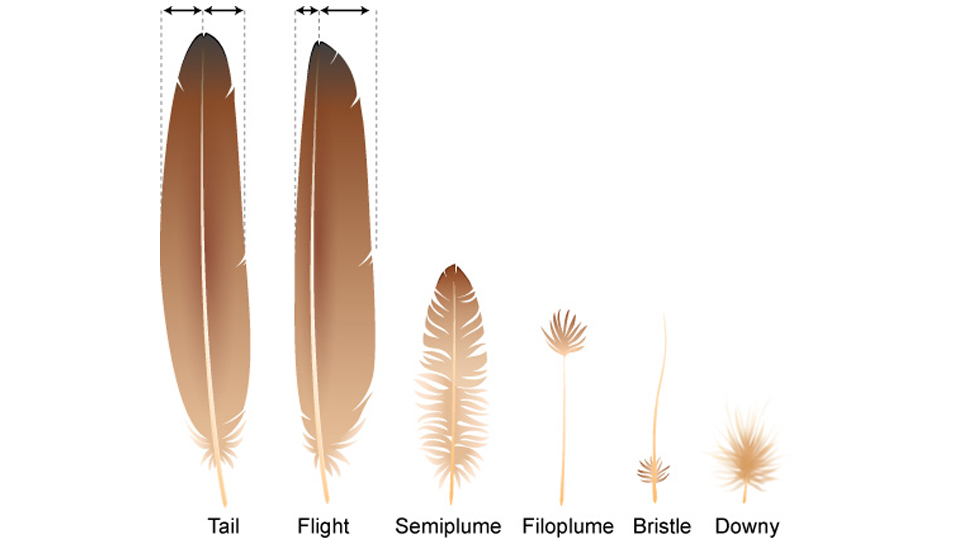

Types of Feathers

Five types of feathers (Tail and wing feathers are both flight feathers and coverts aren’t shown here). Image courtesy Ask a Biologist.

The feathers we find on the ground are usually tail and flight feathers. They seem very similar until we look more closely at them. Central tail feathers are balanced evenly left and right of the rachis, while flight feathers have a wider and narrower side, which lets them cut through the air without twisting. Mostly hidden beneath other feathers on the body, semiplume feathers have a developed central rachis but no hooks, creating a fluffy insulating structure. They also help waterfowl float by trapping air, or sink by becoming waterlogged. Birds use their simple bristle feathers to sense threats and keep dust, grass, insect legs, and other debris from damaging the delicate tissues of their eyes, nostrils, and mouths. Filoplume feathers are associated with sensory receptors in a bird’s skin and are thought to provide information about wind, air pressure, and feather movements that birds use to maintain efficient flight.

Although feathers seem light, all of them put together weigh roughly two or three times more than a bird’s skeleton does. They also require a lot of maintenance. Most birds have a preen gland near their tails. This gland secretes oil which they spread over their feathers with their beaks. Preening helps remove dust, dirt and parasites from feathers and also aligns them properly. Even with care, feathers eventually begin to suffer damage and must be replaced through molting – an itchy-looking process that renders some birds (but not eagles) flightless. However, the benefits of feathers – flight, protection, insulation, display – far outweigh their costs. We sleep warm in our beds with the benefit of furnaces and blankets. All birds need are their feathers.

For more information on feathers, visit https://academy.allaboutbirds.org/feathers-article/. I also took some information from Colin Tudge’s book The Bird.

The Raptor Resource Project

The Raptor Resource Project The Raptor Resource Project

The Raptor Resource Project