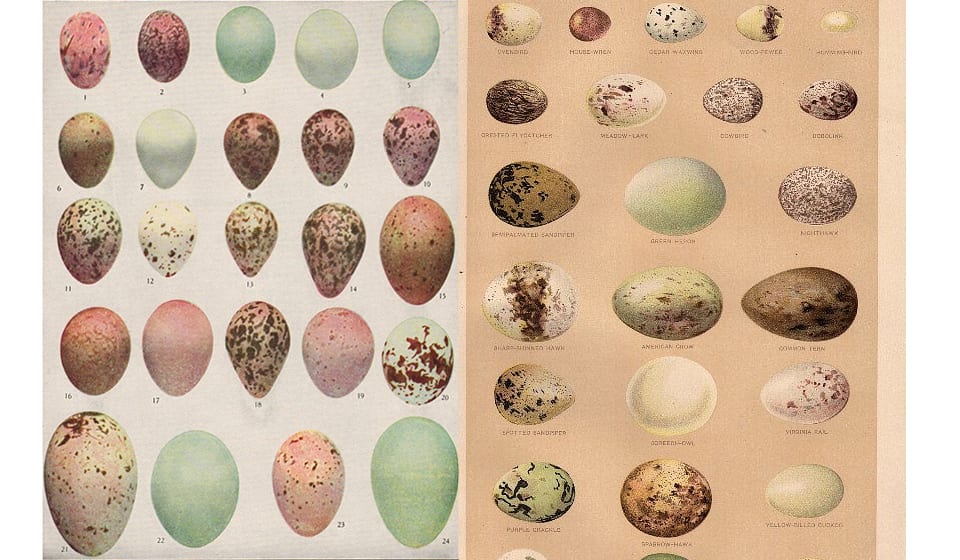

The Chicago Peregrine Program inspired me to write a quick blog on the colors and shapes of eggs. Bald eagles have white eggs, peregrine falcons have eggs that range from light cream through brick red, and red-tailed hawks have pale eggs that are lightly splotched with brown. How and why do the birds we watch lay differently-colored and shaped eggs?

Eggs of American Birds

Egg Colors

Where do egg colors come from? Once a bird’s egg enters its shell gland or uterus, it is plumped with water and covered with calcium carbonate, a chalky white substance that forms the egg’s hard shell. In birds that color their eggs, pigments mix with the last layers of calcium carbonate to form the egg’s ground color. Blotches, spots, streaks, and squiggles are applied as the egg presses against a layer of epithelial cells in the shell gland, causing them to release or squirt pigment on the developing shell. If the egg is stationary or moving very slowly, it will be solid, blotched, or spotted. If the egg is in motion, it will be streaked. And if the bird was startled during pigment deposition, the egg might have a distinct pale or uncolored band around its middle.

Peregrine falcon eggs at Great Spirit Bluff. These red, lightly speckled eggs seem very visible to us, but a predator who couldn’t resolve images in the dim light of a traditional eyrie would have a hard time spotting them – especially with angry peregrines swooping at them!

Coloring eggs carries a metabolic cost, so why aren’t all bird eggs white? Birds that lay white or nearly white eggs might not be as vulnerable to egg predation. They might conceal their eggs in deep cavities or vegetation (owls and geese), nest in large colonies (albatrosses) live in an area free of specialist egg predators (Emperor penguins), or be too dangerous to approach during incubation (bald eagles). Birds that lay colored eggs might be more vulnerable to egg predation. They might not begin incubating right away (peregrine falcons), might live in an area with large specialist egg predators (boreal songbirds), or might build nests that are accessible to predators. A peregrine’s reddish, speckled eggs are difficult to see from a distance, especially for predators with low visual acuity in dim light. Ten or 20 seconds isn’t long, but any delay might buy enough time for enraged parents to drive nest intruders away.

Egg Parasites

Egg eaters aren’t the only threat to eggs and young. Some birds dump or lay eggs in the nests of other birds. Splotched, spotted, or streaked eggs might help individual birds recognize their own eggs and reject eggs that don’t match them. So why don’t Canada geese, which egg-dump, lay patterned or marked eggs? In this case, non-parental eggs probably don’t impact the survivability of parental eggs. Canada geese are precocial, so young require less parental investment once the eggs hatch. They also don’t stay in the nest very long, so an egg dumped at the wrong time won’t survive.

Egg Shapes

Why are eggs shaped the way they are? Peregrine falcons, Bald eagles, and Red-tailed hawks lay differently colored eggs, but the eggs of all three species are elliptical or oval in shape. We used to think that egg shape was influenced by clutch size, egg stacking, calcium availability, and/or ‘the roll factor’ – i.e., heavily tapered eggs roll in a tight circle instead of rolling off ledges. But in 2017, Professor Mary Caswell Stoddard and her team found that the shape of an egg correlates with the hand-wing index, a measure of the shape of the wing. Fast, frequent flyers have longer, narrower, pointier wings and longer, narrower, pointier eggs. Slower, less-frequent fliers have shorter, broader, more rounded wings, and shorter, broader, more rounded eggs.

Why would flying ability influence an egg’s shape? The maximum size or width of a stretched oviduct is constrained by a bird’s body size. Faster, frequent flyers have thinner bodies and smaller abdominal cavities relative to slower, less-frequent fliers. Their muscular, streamlined body plans and narrower oviducts can’t accommodate large, round eggs, but their eggs still have to carry enough nutrients to support embryonic development. These birds maximize egg volume by forming elliptical or asymmetrical eggs that can pass through their narrow oviducts while carrying the nutrients that their embryos need to develop and grow.

How do birds form asymmetrical eggs? I used to think that eggs were shaped by their stiff outer shells, but it is an egg’s inner membrane that determines its shape. Birds that form elliptical or asymmetrical eggs lay down a membrane that is thicker on the big end and thinner on the pointy end. As an egg moves through a bird’s oviduct prior to eggshell development, the thinner end is squeezed and elongated to produce an asymmetrical egg.

It’s all about survival

In short, egg colors and shapes are all about survival. Factors influencing individual and species-level survival might include health (healthier birds tend to lay more vibrant eggs), resource availability, metabolic cost, the need to hide from predators, the need to identify one’s own eggs, and the shape imposed on an egg by the parent bird’s body plan. Over tens of thousands of years, the birds that survive pass their traits, including egg color and shape, down to the next generation. Like so much else in a bird’s life, the color and shape of its eggs have a story to tell.

Things that helped me learn and write about this topic:

For more on birds of prey and body plan, read this blog: https://www.raptorresource.org/2023/01/20/body-plans-and-shapes-identifying-birds-in-flight/

The Raptor Resource Project

The Raptor Resource Project The Raptor Resource Project

The Raptor Resource Project