Since we weren’t able to get to everyone’s questions during our chat on Explore, we answered them here. Watch the full chat here! https://youtu.be/MCtdzn13aSI.

How do eagles keep their feet from freezing?

An eagle’s legs use counter-current heat exchange to control body temperature. Warm arterial blood flowing from an eagle’s core into its feet passes cool venous blood flowing the other way. Heat is exchanged, warming the blood flowing into its core and cooling the blood flowing into its feet. The cooler blood is still warm enough to prevent frostbite, but the lower temperature reduces the gradient between its insides and its outsides, preventing excessive heat loss through its feet. It has very few soft tissues in its long legs and feet, which are wrapped by thick, scaly skin that helps protect them from the cold. If its feet do get cold, it can always tuck them underneath its feathers. You can learn more about an eagle’s response to cold here: https://www.raptorresource.org/2019/01/17/flashback-blog-how-do-eagles-stay-warm-in-cold-weather/.

Why do parents sit on hatchlings?

A hatchling eaglet can’t thermoregulate, or control its temperature, so parents need to brood or sit on them to keep them warm. At ten to 15 days, dense ‘woolly’ thermal down begins to replace fuzzy white natal. Thermal down provides more insulation and helps nestling eaglets keep their body temperature relatively constant. However, thermal down isn’t as weatherproof as feathers, so they still might need brooding in extremely cold or wet weather.

Do bald eagles migrate or are they sedentary?

Some eagles migrate and some don’t, and eagles may undertake winter and summer migrations. Let’s start with the Decorah Eagles. As far as we know, every eagle on that territory has been a year-round resident. They have wonderful habitat and ample access to food during the winter, so they don’t leave. However, all of their young dispersed from the territory (even if D24 didn’t disperse very far) and at least two of them have made long migrations between their wintering grounds (Iowa) and summering grounds (Ontario). Adults tend to be more sedentary than sub-adults, although some (think eagles in central Canada or the US northern boreal forest) still migrate when winter begins to bite. You can follow the travels of all of the eagles we’ve tracked here: https://www.raptorresource.org/learning-tools/eagle-map/.

Do eagles have any predators?

Adult bald eagles don’t really have predators – i.e. something that specializes in hunting and eating them, or relies on them as a food source. While nothing specializes in taking nestling eaglets, raccoon will eat eggs and young (raccoon will eat everything they can get their paws on!) and owls will take young if they have a chance. We’re not sure that owls deliberately attack nests to take young, though – they might attack nests out of instinct or territoriality and take young secondarily.

Why do they nest without shade or shelter from elements? Why do they have white heads?

Eagles tend to nest toward the tops of trees, or on open cliff faces, because they need a lot of room to fly in and out, especially when carrying large sticks. Denser leaves and brush might provide more protection, but it would also be more difficult for them to access and build nests. Either way, there is no foliage when eagles begin nesting in Iowa, Minnesota, and Wisconsin, regardless of where they are nesting.

In general, researchers think that adult eagles have white heads to help them distinguish sexually mature individuals at a distance. However, John pointed out that their white heads and tails would make them more cryptic during incubation, especially if they are nesting in snow-covered nests. This is an interesting idea and one worth exploring.

Do the nesting habits of eagles match any weather patterns?

There are two ways to think about that question: nesting chronology, or the time at which nesting occurs, and short-term response to immediate weather conditions.

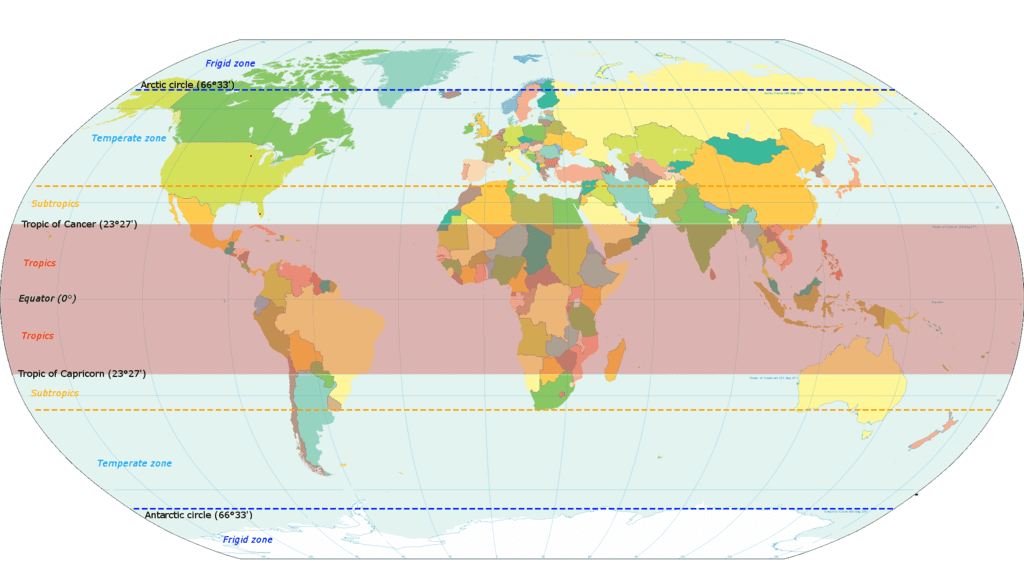

Let’s start with nesting chronology. Nesting chronology is determined by daylight length, ice cover, and intensity. Daylight length appears to be a bigger factor among birds that nest in the temperate and frigid zones, while daylight intensity may play a bigger role among birds that nest in the subtropical and tropical zones. However, eagles that nest in temperate and frigid areas are also influenced by ice cover, which can vary quite a bit from region to region. Eagles that nest in Canada and Wisconsin’s Lake Country will usually nest later than eagles nesting next to water that is open year round (parts of the Mississippi River, parts of the Saint Croix River, Decorah).

Ice cover seems pretty obvious, since eagles can’t catch fish beneath the ice and female eagles need to build up their fat, calcium, and water reserves to lay eggs. But why does daylight length make a difference? Birds need to be light to fly. During most of the year, their gonads are shrunken and inactive. But when daylight length increases following winter solstice, or daylight intensity increases following the end of the rainy season in tropical latitudes, a bird’s gonads ‘wake up’ and begin swelling. Sex hormones course through their bodies, which leads to nesting, sperm, eggs, and young.

The Decorah and Decorah North eagles nest next to open water and will lay eggs in February or March regardless of temperature, windchill, or snowfall. However, weather can push laying a tiny bit earlier or later. We’ve documented both couples laying eggs three to four days later in very cold, dry temps. This might be because females need to store a lot of water to produce an egg, and cold dry weather makes that harder.

What about Bald Eagles in Florida?

The SW Florida eagles are well within the sub-tropical zone, so their reproductive activity is most likely influenced by light intensity instead of daylight length.

World map showing tropic, subtropic, temperate, and frigid zones

Average monthly rainfall ramps up in early May and stays high through mid-September. What comes with rain? Clouds! What is diminished by clouds? Light intensity! Light intensity begins rapidly increasing in September, causing gonads to swell and eggs to be laid in November or very early December instead of February or March.

Like their northern counterparts, the SWFL eagles will lay eggs regardless of immediate weather conditions like rainfall or bad storms. John brought up a nesting eagle’s immediate response to weather conditions. Nesting eagles respond to external weather conditions by changing their wing configuration in inclement weather to protect the eggs from snow, sleet, and rain, adding fresh nesting material to keep eggs warm and dry, standing off the eggs to air and cool them, keeping them completely covered in very cold or wet weather, and so on. We’ve written extensively about nesting chronology. Here are a few links for anyone who wants to learn more!

Just wondering why the eggs on the Decorah nest are different colors? I always thought their eggs were all white.

Egg color can change from near white by picking up staining or tannins from the nest material, prey items in the nest, and dirt, to name a few. The degree of color change is related to how long the eggs are in the nest. We have seen a significant difference in the color and darkness of the eggs at the Decorah Fish Hatchery nest this year. It was fairly easy to tell the difference between the oldest (more dark and dirty) to the newest egg.

The Raptor Resource Project

The Raptor Resource Project The Raptor Resource Project

The Raptor Resource Project