Where did the Steller’s Sea Eagle in Massachusetts come from? No legal zoo or individual in the United States reported a missing Steller’s Sea Eagle, but we can’t rule out an escape from an illegal menagerie. This blog assumes the eagle made a one-of-a-kind flight from the Kamchatka Peninsula in Russia to the Western Hemisphere. We hope that is the case!

We’re getting a lot of questions about the Steller’s Sea Eagle last seen in Massachusetts. How did it get here? How often do they come to the United States? Will the eagle ever return home? Here’s what we know, what we might be able to infer, and how rare it is to see one in the Western Hemisphere.

About Steller’s Sea Eagles

Steller’s Sea eagles (Haliaeetus pelagicus) are members of the genus Haliaeetus, or fish eagles, a genus that includes the Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus Leucocephalus). While they aren’t the longest eagle in the world, they are the heaviest: a large female might weigh as much as 19 pounds! Like the rest of their genus, they prey primarily on live fish, although they will also eat birds, mammals, and carrion. Steller’s Sea Eagles build large stick nests, lay 1-3 eggs, and are very gregarious off their nesting territories.

Sound familiar? Here’s a difference: Bald Eagles have learned to exploit human-based food resources like confined feedlots and landfills, while Steller’s Sea Eagles always nest near water containing fish. Their nesting habitat might reflect their large size and remote environment. A 19-pound eagle requires a lot of space for lift-off and hunting, and confined feedlots and landfills aren’t part of a Steller’s Sea Eagle’s world. Humans are rare in the remote stretches of the far north.

General Location and Migration

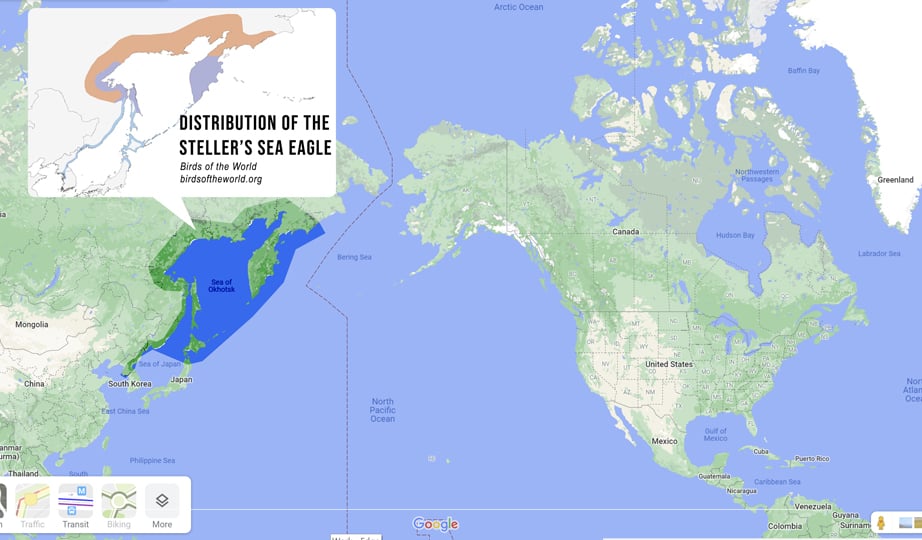

Distribution of the Steller’s Sea Eagle. See resources section for link.

Steller’s Sea Eagles are partial migrants who breed primarily along the sea of Okhotsk. Migrating birds might loop the sea of Okhotsk, move to the southern part of the Kamchatka peninsula, winter on the Japanese island of Hokkaido, or head south to the Koreas. There are just 38 Steller’s Sea Eagle sightings recorded in the Aleutian Islands chain between 1917 and 2021: a small fraction of the hundreds of sightings reported on the species’ typical range. Most western hemispheric reports are relatively new, which could reflect range changes and/or increased accessibility to the western range of wandering migrants. Like bald eagles, Steller’s juveniles and sub-adults wander more widely than adults, and some birds wander more widely than others.

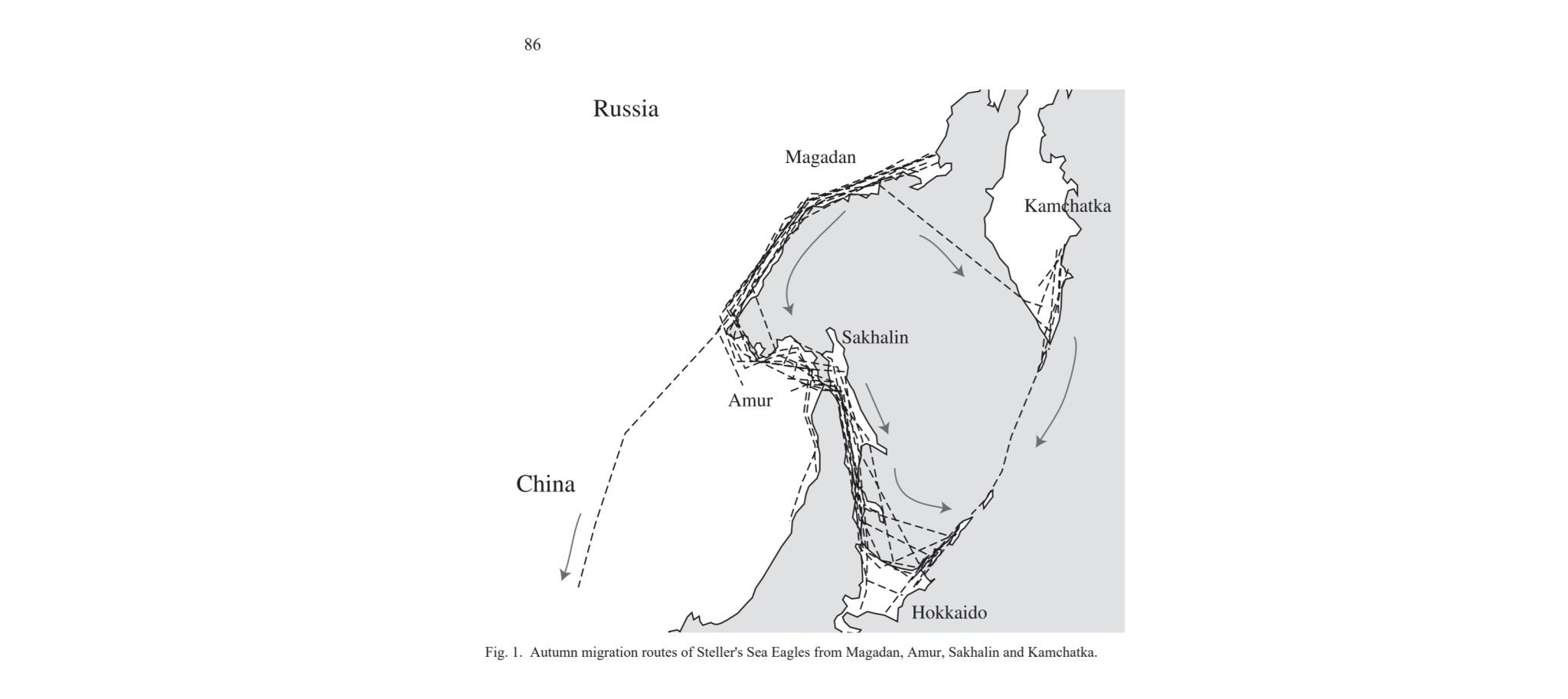

Typical Migration and Wintering of Juvenile and Immature Steller’s Sea Eagles. See resources section for citation

A Mystery, an Enigma, a Story

Even for wanderers, this Steller’s Sea Eagle is a real outlier. Based on what we know, it probably hatched at the northern end of the species’ breeding range. It could have flown to the United States along the Aleutian Islands, a chain that stretches like steppingstones between the Kamchatka Peninsula and southern Alaska, or it could have flown north along the coast and crossed at the Bering Straits. Compared to the 800-mile gap between southern Kamchatka and northern Hokkaido, 50 miles over the Bering Straits would be a walk in the park! Even the longest gap in the Aleutians (a little over 200 miles between an unnamed island and Attu Station), is just a little over double the longest gap in the Kuril Islands. Sea eagles are capable of traveling very long distances, even though it is beyond rare to see one in the eastern United States.

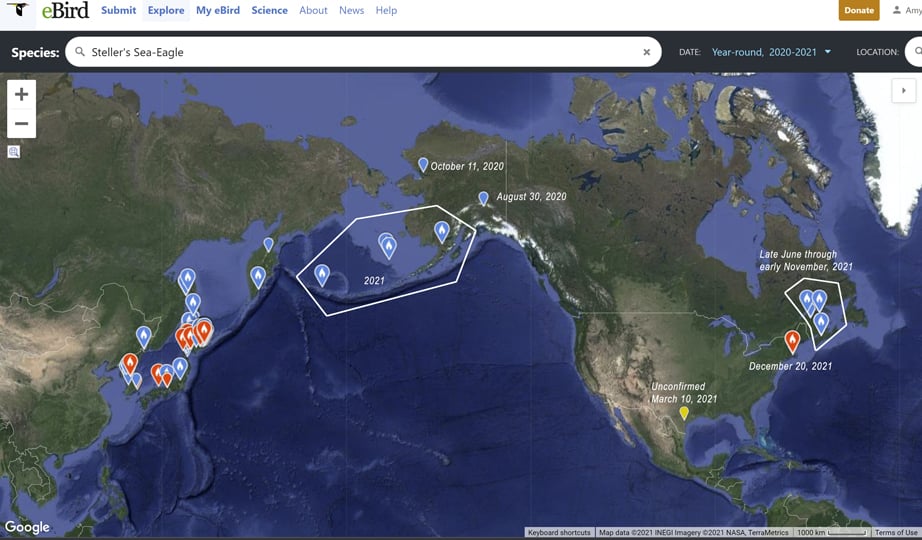

2020-2021 reported sightings of Steller’s Sea Eagles. Note that the 2021 sightings in the Aleutian Islands could not be the eagle currently on the east coast given the timing. See resources section for eBird link.

Where Did It Do Once It Got Here?

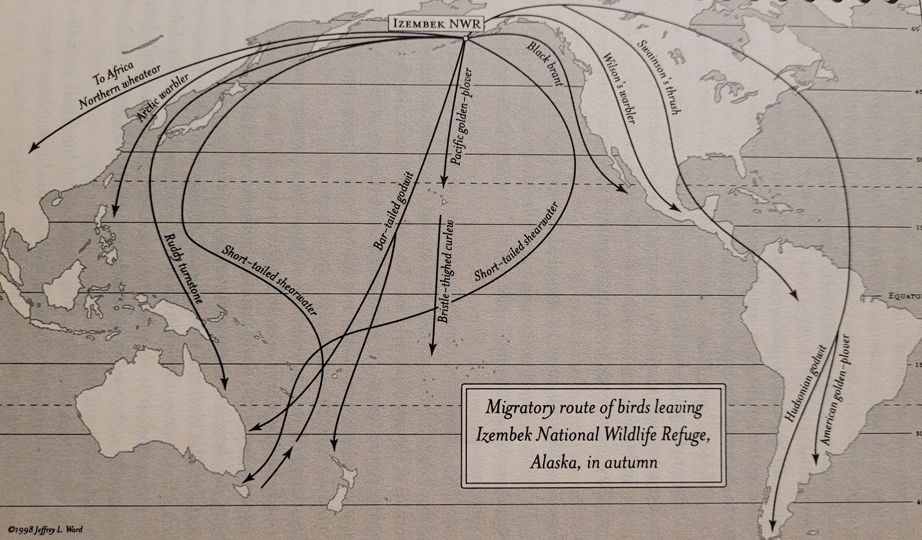

What did the eagle do after it got to the Western Hemisphere? If it crossed at the Aleutians, it might have stopped at Izembek National Wildlife Refuge, a global crossroads for many migrating species. It could have seen grey whales that migrated north from Baja, followed salmon coming back to their natal streams from Japan and Korea, or flown over breeding birds headed for the Philippines, Australia, Africa, and south-eastern South America. If it crossed at the Bering Straits, it might have flown over the Bering Land Preserve, which lies at the convergence of three major migratory flyways. Long-distance migrants depend on unique, widely spaced islands of habitat that are often at the center of resource extraction and development arguments. Call it a miracle or call it an entangled bank – however you think about it, we need to leave places like this to them.

Map by Jeffrey L. Ward, from Scott Weidensaul’s book Living on The Wind. Places like this are beyond important! See resources section for citation.

Steller Sea Eagle spotters reported two confirmed sightings in 2020: one near the Maclaren River in south central Alaska on August 30, and one near the Bering Straits on October 11. Another sighting was posted to Facebook from a location in southern Texas on March 10 of 2021. Was it real? I can’t say that the eagle didn’t end up in Texas, 10 degrees south of the species’ southernmost known latitude, but I can’t say that it did. An enigma doesn’t need a straightforward story, but birding reports like this need a lot of proof. One unconfirmed, unsourced photo posted to a Facebook page doesn’t cut it.

So How Did it Get to the East Coast?

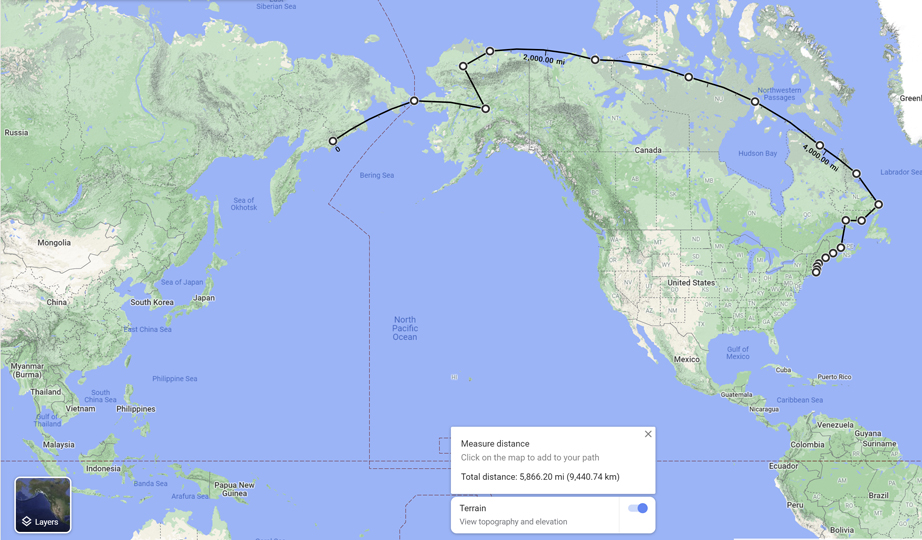

Based on what we know about Steller’s Sea Eagles, the eagle probably wintered somewhere in or near the Aleutian Islands, at about the same latitude as the species’ year-round habitat on the Kamchatka Peninsula. How did it get to the eastern seaboard? Research shows that Steller’s Sea Eagles migrate along the coast. One (totally speculative!) potential route follows the Arctic Ocean coastline all the way across the top of North America, crossing the gap at the north end of Hudson’s Bay and dipping down the eastern seaboard to western Quebec, Nova Scotia, and finally Massachusetts – a journey of 5,866 miles. It looks like this:

One possible route: a WAG based on transmitter studies and eagle observations.

Most of this route is extremely remote, allowing the eagle to pass unnoticed through regions almost entirely devoid of people. What did it think about eastern Massachusetts? What was it like being in a region so different than anywhere it lived or traveled through? What is it doing there? I wish we could know.

Will The Sea Eagle Ever Go Home?

It’s impossible to know. If the western Alaska and Massachusetts sightings are of the same bird, it is a complete enigma: a one-of-a-kind story that we can’t compare to any other. Scott Weidensaul mentions birds born with a faulty internal compass: birds who travel to the wrong place or can’t stop migrating. If this is the case, it probably won’t fly back home, and might not stay there if it does. The sea eagle is still living its story – whatever that is – and it’s unlikely we’ll get to know the ending. We wish it the very best!

The more people report bird sightings and band numbers, the more we learn about the lives of birds. Keep your eyes to the sky (or the ground, or the surf, or the lake) and:

Things to Think About!

- There are a lot of similarities between Bald Eagles and Steller’s Sea Eagles (did anyone else think of bald eagles on the Flyway when they watched that video?), but juvenile bald eagles disperse before their parents migrate, while adult Steller’s Sea Eagles migrate before their young disperse. This behavior appears to be common among arctic and near-arctic birds. I assume it has something to do with the scarcity of resources as winter approaches: more birds gone means less competition for food resources. But why do parents leave first? I would love to know more!

- Could Steller’s Sea Eagles be changing their habitat and/or migration routes? A European found rapid evolution of new migration paths in Blackcaps. Here in the United States, we’ve seen rapid changes in the migration of rufous hummingbirds, anna’s hummingbirds, Canada Geese, Snow Geese, and other species. One very-out-of-range eagle does a trend make, but I found it interesting that most western Aleutian sightings occurred relatively recently. Even as I write, people are reporting another Steller’s Sea Eagle over in the Western Aleutians.

Resources and Citations

- Brett Mandernack, personal communication. Thank you for your help in reviewing and thinking through this blog!

- eBird: www.ebird.org in general. https://bit.ly/3HoRfZE for records of all Steller’s Sea Eagles reported to eBird.

- Birds of the World: https://www.birdsoftheworld.org, https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/species/stseag/cur/introduction#repro for more about Steller’s Sea Eagles.

- Mcgrady, Michael & Ueta, Mutsuyuki & Potapov, Eugene & Utekhina, Irina & Masterov, Vladimir & Fuller, Mark & Seegar, William & Ladyguin, Alexander & Lobkov, Eugene & Zykov, Vladimir. (2000). Migration and wintering of juvenile and immature Steller’s Sea Eagles. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259009148_Migration_and_wintering_of_juvenile_and_immature_Steller’s_Sea_Eagles

- Book: Migrating Raptors of The World: Their Ecology and Conservation, by Keith L. Bildstein

- Book: Living On The Wind: Across the Hemisphere With Migratory Birds, by Scott Weidensaul. Do yourself a favor and buy all of his books! Seriously.

- The Kuril Island Chain: https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/44578/southern-paramushir-island-kuril-chain-russia. Steller’s Sea Eagles migrate over and live in some really cool places! Take a deep dive and learn more about one of the wildest places on earth!

- Bering Island Land Bridge National Preserve: https://www.nps.gov/im/arcn/bela.htm. #BeringiaForever

The Raptor Resource Project

The Raptor Resource Project The Raptor Resource Project

The Raptor Resource Project