At whatever moment you read these words, day or night, there are birds aloft in the skies of the Western Hemisphere, migrating. If it is spring or fall, the great pivot points of the year, then the continents are swarming with billions of traveling birds…

– Living on the Wind: Across the Hemisphere with Migratory Birds

It’s 98 degrees outside my window right now. Bees are humming in the goldenrod, leaves are just beginning to change colors, and birds are stuffing themselves silly on the seeds of sunflower, thistle, black-eyed susan, and hemp. It doesn’t feel like fall, but my birdfeeder needs to be refilled every three days or so and I’m seeing more birds in my yard. While some birds are still preparing for migration, others are beginning to wing their way south!

Keep your eyes on the Flyway!

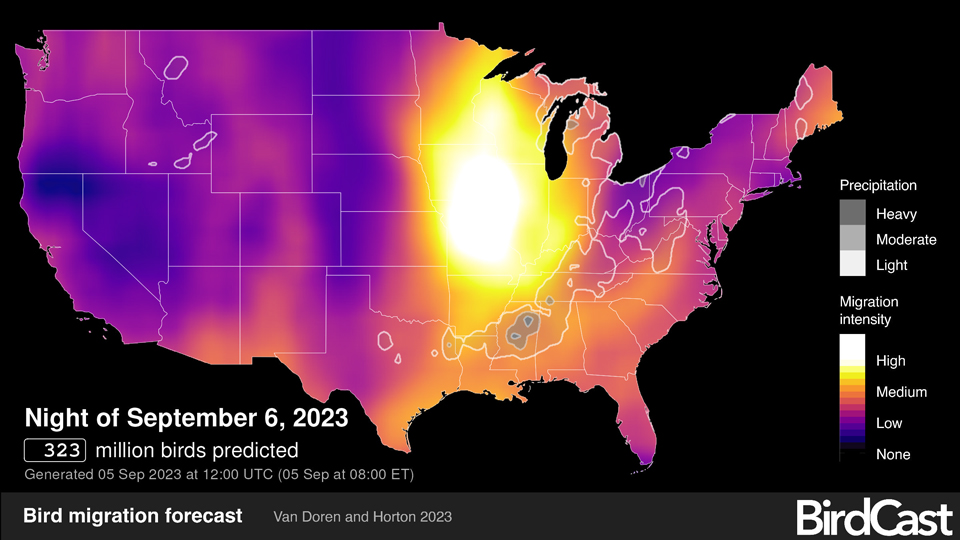

Birdcast predicts a heavy night for September 5th and 6th in the area of the Flyway. Listen for nocturnal migrants at night and look for nocturnal and diurnal migrants resting and feeding during the day. I’ve got my fingers crossed for some spectacular flights in and out of the Big Lake.

Birdcast migration prediction for September 6, 2023. That’s a lot of birds!

Birdcast migration prediction for September 6, 2023. That’s a lot of birds!

When and where do birds migrate? A BirdCast data compilation revealed that the top five states for migration in 2021 were Georgia, Alabama, Missouri, Iowa, and Texas! Iowa benefits from having a long eastern coast on the Mississippi River, America’s third biggest Flyway, and a sizeable western coast on the Missouri, which drains the great plains east of the Rockies and connects with the Mississippi just north of the city of St. Louis. The same study found three big migration peaks: one on September 22, one on October 3, and one on October 16. All three peaks followed high pressure systems that brought cold weather and favorable tailwinds out of the north, although researchers think there was a difference in the makeup of species. Peak one likely consisted of long distance or leapfrog migrants that have a lot of ground to cover, while birds that stay in the US have less distance to cover and so migrated later. Not mentioned: the incredible arrival of Tundra Swans and Bald Eagles that we see on the Flyway in late October through mid-November.

Migration Basics

August 30, 2023: Caspian Terns on the Flyway

August 30, 2023: Caspian Terns on the Flyway

I used to think migration was very simple. Like a lot of people, I thought that all birds except chickadees, pigeons, crows, and woodpeckers migrated once it got cold. They went south to escape snow and ice, returning to nest when the weather warmed up. ‘South’ was anywhere it didn’t snow, or at least didn’t snow much: Georgia, the Gulf Coast, South America. I had no idea that many birds don’t migrate, that members of many species have very different migratory behaviors, or that ‘south’ could be Minnesota or Wisconsin. Peregrines, Snowy Owls, and Bald eagles taught me otherwise.

August 28, 2023: A Merlin on the Flyway

August 28, 2023: A Merlin on the Flyway

Among birds, migration is the regular, endogenously controlled, seasonal movement of birds between breeding and non-breeding areas (Salewski and Bruderer 2007). Bald eagles and Peregrine falcons are partial migrators – that is, some members of the species migrate and others don’t. This is the most common type of migration, which makes sense since migration is driven by a number of factors, including daylight length, food availability, weather, the time it takes to raise young, and the distance between wintering and breeding grounds. Migration allows exploitation of different habitats as environments change (Dingle, 1996). Food availability seems to play a very important role in the migration of Bald eagles: inland northern Bald eagles tend to move southward after ice and snow start putting a lid over their favorite food source – fish – while southern Bald eagles are thought to move northward once warm weather drives fish into deeper water (although there is some debate about this). Weather can also impact migration timing in other ways: for example, a favorable wind pattern might help compel a bird to leave for its wintering or summering grounds if other factors are in place.

August 31, 2023: Waterfowl against a full Flyway moon. Full moon counts are still sometimes used to gather data on nocturnal migrants.

August 31, 2023: Waterfowl against a full Flyway moon. Full moon counts are still sometimes used to gather data on nocturnal migrants.

I also thought that birds traveled the same path backwards and forwards. However, it turns out that many birds, including several of our eagles, favor loop migrations. This might be a response to prevailing winds, food availability, tradition, and/or genetic influence. More to the point, loop migrations require more complex navigational skills (and perhaps inheritances) than a simple point A to point B path.

How Do Migrating Birds Navigate?

So how do birds navigate? Migration studies have found five major methods:

- Magnetic sensing: Some birds (perhaps all birds) are able to use the direction and strength of Earth’s magnetic fields to orient themselves. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/27/science/study-sheds-light-on-how-pigeons-navigate-by-magnetic-field.html?_r=0

- Geographic mapping: When I’m in Minneapolis, I use a number of tall buildings to help me orient the city. It turns out that birds do the same thing, using landforms and geographic features such as rivers, coastlines, and mountain ranges to guide them.

- Celestial navigation: migratory birds use the position of the sun (during the day) or the rotation of stars (at night) to orient themselves. Experiments done by Dr. Emlen in 1967 indicate that celestial navigation is learned. http://www.birds.cornell.edu/AllAboutBirds/studying/migration/navigation

- Wind patterns: A recent study at Cornell using crowdsourced data found that passerine birds are heavily dependent on wind direction for migration. By shifting routes, birds take advantage of stronger tailwinds in spring and less severe headwinds in fall.

- Learned Routes: Some bird species, such as sandhill cranes and snow geese, learn migration routes from their parents and other adult birds in the flock. Once younger birds learn the route, they can travel it by themselves and transfer that knowledge to their own children!

What do Bald eagles and Peregrines do? They most likely use multiple sources of information, including celestial and magnetic clues, light polarization, wind patterns and direction, and geographic cues. Although parents and young don’t migrate together that we know, we have often seen our tracked eaglets in the company of other eagles, which suggests that following might play a role as well.

September 5, 2023: Newman at Great Spirit Bluff

September 5, 2023: Newman at Great Spirit Bluff

In addition to watching our eagles, keep an eye on the animals outside your window. We know fall is here, and so do they.

- Birds are gathering in huge premigratory flocks, gorging on food to build fat reserves, and exhibiting restlessness, also known by the marvelous word zugunruhe. These behaviors help prepare birds for migration. Keeping a well-stocked bird feeder helps them, as does turning out lights at night. Check out Audubon’s Lights Out program, which includes tips for keeping birds safe and ways to connect with other people on this issue: https://www.audubon.org/conservation/project/lights-out

- Frogs and turtles are migrating from summering breeding grounds to deeper bodies of water. While their travels are short, they still fit the definition of migration. For more on frog hibernation, click here. The Minnesota DNR has a very good article on helping migrating turtles cross roads, some cities close roads, and volunteers help keep migrating frogs safe.

- Some insects migrate and others hibernate. Aggregating paper wasps may be getting ready to hibernate, while dragonflies migrate in large numbers (check this source out). We saw migrating dragonflies out by the North Nest in September!

Watch out for migrating Mule deer! According to National Geographic, they make a 150-mile migration twice yearly from the low desert to the high mountains.

Have a happy fall and take the time to watch for migrating birds and other animals! Would you like a migration forecast? Check birdcast out! https://birdcast.info/

Resources and Links

Some things that helped me write this post:

The Raptor Resource Project

The Raptor Resource Project The Raptor Resource Project

The Raptor Resource Project