Each species experiences the world differently and eagles have capacities that are far different from ours. How do Bald Eagles survive an Iowa winter without adaptive clothing and central heat?

A cold January morning coated our eagles in frost and left watchers wondering how Bald Eagles survive an Iowa winter. In general, wintering animals – including humans – need to retain body heat, stay dry, and take in enough calories to support winter’s increased energy demands. We humans put on adaptive clothing and heat our buildings and vehicles. Bald eagles reduce activity, seek and create protective microclimates, manipulate their temperature, forage and roost in groups, gorge food, and increase their assimilation of food energy. In short, Bald Eagles use the ultimate eagle super power: maximizing energy gain and minimizing energy loss. This is especially important when the temperature drops below 51.1F – much warmer than an Iowa winter! At 51.1F, an eagle’s metabolic rate begins to increase, which drives its need to minimize energy expenditure and select habitat that reduces heat loss.

Staying Warm

It’s -25F as we trudge up a snowy pre-dawn Driftless hill to set Golden Eagle traps. I’m wearing knee-high snowmobile boots, long underwear, pants, a sweater and jacket, a turtle fur, a hat, and gloves. My exposed skin stings with the cold. How do eagles stay warm in temperatures like this?

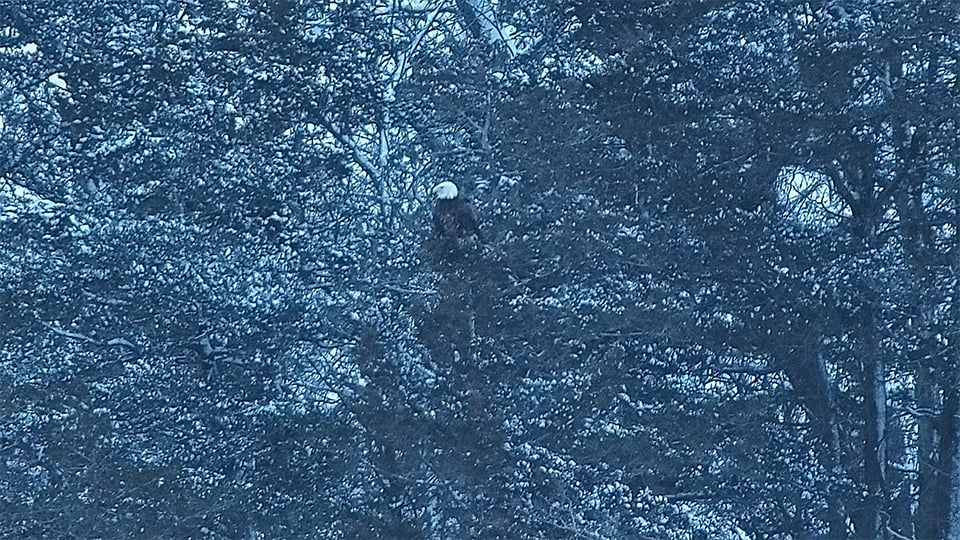

January 23, 2023: An icy fog left everything coated with frost, including HM and HD.

Good Insulation

Two layers of feathers keep bald eagles warm and dry through winter’s deepest cold and icy rain. Stiff exterior covert feathers zip together over fluffy down feathers: an overcoat that channels water away from an eagle’s down and skin, absorbs solar energy, and reduces energy loss. Beneath the coverts, layers of down trap and hold warm air. When we’re cold, a specialized muscle at the root of our body hair erects and gives us goosebumps: an involuntary reaction that doesn’t help us very much. But the same reaction fluffs out a bald eagle’s feathers, which increases the depth of warm air that surrounds it and keeps it toasty even in subzero temperatures. How toasty? Researchers found that kinglets – a tiny little bird! – can maintain a body temperature up to 133F warmer than the surrounding temperature.

I take off my gloves to help set up some equipment. My fingers quickly become stiff and numb as I fumble with knots and latches. How do eagles keep their toes nimble in below-zero weather?

An eagle’s leg muscles are tucked up under its feathers, near the warm center of its body. It has very few soft tissues in its long legs and feet, which are wrapped in thick, scaly skin that protects them from the cold. If its feet get cold, it will tuck them beneath its feathers to warm them up!

January 25, 2023: HD and HM tuck their heads and feet in to minimize heat loss and protect bare skin.

Built-in Counter Current Heat Exchange

If my core cools down too much, my body will drastically reduce blood flow to my hands and feet to decrease heat loss and protect me from hypothermia. A bald eagle’s body is insulated, but its naked legs are bare. How does it maintain a safe core temperature and keep its bare feet and legs from freezing or leaking too much heat?

The arteries and veins in a bald eagle’s legs run close together. Cold venous blood returning to an eagle’s core wicks heat away from warm arterial blood flowing to its feet. Outgoing arterial blood is cooled to just above freezing: cold enough to minimize radiative heat loss and warm enough to prevent frostbite. Incoming venous blood is warmed well above freezing, which protects its core from excessive cooling.

As Berndt Heinrich points out, we humans keep our feet warm at a high energy cost. Birds keep their foot and leg temperatures just above the freezing point, which reduces their energy burden.

Changes in Blood Flow and Body Temperature

Counter current heat exchange and feathery insulation aren’t always enough to keep an eagle warm. In winter’s world, every calorie is critical. A few calories might mean the difference between life and death.

Cold temperatures change how blood flows through an eagle’s body. Like us, eagles reduce blood flow to their bare skin and extremities, which limits radiative heat loss and increases the amount of blood available for absorbing and transporting calories from food. At night, a bald eagle lowers its body temperature. This reduces the temperature difference between its body and the outside world, which lets it burn fewer calories to stay warm.

Seeking Protective Microclimates and Reducing Activity

January 26, 2023: Cedar boughs and tangled branches reduce convective heat loss

I’m so glad we’re almost done. The wind won’t quit and the goat prairie offers no rocks, trees, or brush to hide behind. I turn my face south to shelter it from the icy breeze and look forward to a hot cup of coffee and a nice long rest once we’re done.

When temperatures drop, eagles reduce their activity and seek protective microclimates for perching and foraging, including densely tangled branches, pine boughs, and the lee side of rocks and trees…anything that reduces conductive heat flow from their bodies to the relentless heat sink of the sky and the wind.

HM and HD sometimes perch on a low branch near the creek on the west side of Hatchery Rock. The deeply incised valley and weedy cottonwood limbs shelter them on all but the blusteriest days. It’s a wonderful place to perch, hunt, and stay out of the wind.

Group Foraging and Changes in Behavior

January 14, 2021: Eagles at Lock and Dam Seven on Lake Onalaska, Mississippi River

All bald eagles reduce activity and seek shelter during periods of extreme cold. Non-territorial eagles also forage in groups and roost communally to help conserve energy.

When one eagle finds food, every eagle finds food. Wintering non-territorial bald eagles commonly forage in groups, which lets them find more food with less work than hunting alone. They also steal prey from other eagles, which can be more energy efficient than catching it themselves. Why go fishing when someone else can do it for you?

But group foraging also presents a problem. What do you do when almost everyone tries to steal food from you? You eat it before someone else gets it! When eagles eat more food than they can digest, they store the excess in their crops for later. Gorging loads calories quickly and reduces the opportunity for food theft.

Winter is all about balance: the balance between calories in and calories out, between easily finding food and having food snatched away, between doing what needs to be done and limiting activity and exposure in the cold. It’s no surprise that many juvenile bald eagles don’t survive their first winter, or that successful mated couples develop bonds that last over years and miles. It takes hard work, intelligence, and dedication to survive and thrive in winter’s world.

How Can I Help Wintering Birds?

It’s hard not to be concerned about eagles and other wildlife during extremely cold weather. You can help by keeping seed and suet feeders stocked, keeping water available, and providing shelter for birds. The Minnesota DNR offers these winter feeding tips:

https://www.dnr.state.mn.us/birdfeeding/winter.html.

References

- Ecological Energetics and Foraging Behavior of Overwintering Bald Eagles

Mark V. Stalmaster and James A. Gessaman

Ecological Monographs

Vol. 54, No. 4 (Dec., 1984), pp. 407-428

Published by: Ecological Society of America

Article Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1942594

- Food Consumption and Energy Requirements of Captive Bald Eagles

Mark V. Stalmaster and James A. Gessaman

The Journal of Wildlife Management , Vol. 46, No. 3 (Jul., 1982) , pp. 646-654

Published by: Wiley on behalf of the Wildlife Society

Article Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3808555

- Winter World: The Ingenuity of Animal Survival by Bernd Heinrich

Did You Know?

The Raptor Resource Project

The Raptor Resource Project The Raptor Resource Project

The Raptor Resource Project