I thought I would write a little bit about Bald Eagle conservation and recovery in the United States. I think most of our followers are aware of the eagle’s close brush with extinction due to DDT, but that was not the first narrow escape for America’s national bird.

While John James Audubon is celebrated as an artist, naturalist, and ornithologist, he was no friend to the bald eagle, or raptors in general. In the 1830’s, Audubon accused bald eagles of having a cruel spirit and being the “dreaded enemy of the feathered race”. He described raptors overall as being cowardly, tyrannical, and possessed of a hissing, disagreeable imitation of a laugh. Unfortunately, this was a pretty common attitude. Americans loved the eagle as a symbol of freedom and power, but regarded the living bird as a lazy and immoral baby-snatcher, cold-blooded killer, and chicken thief. Eagles were slaughtered by the tens of thousands: If it moves, kill it! embodies the attitude of bald eagle foes.

The First Near Extinction

As eagles were gunned down, American expansion was remaking the landscape. Farms, ranches, cities, and widespread logging erased trees and wildlife habitat, leaving behind a horizon-deep devastation of charred logs and naked stumps, and fouling lakes and rivers with silt, ashes and feces. It quickly became clear that the United States, which had been considered an Edenic, indestructible land by European settlers, was at risk of losing the very things it was celebrated for. ‘Nature’ and ‘natural activities’, including bird feeding and bird watching, came into vogue after the American Civil War. This attitude was driven in part by the plight of the plume trade, the passenger pigeon, and the bison, which made conservation a pressing issue for the first time in modern American life. By 1900, twenty-two states had Audubon Societies, which were organized and driven primarily by society women: upper-class women of leisure who had the time and resources to devote to conservation.

The Migratory Bird Treaty went into effect on August 1, 1918. But raptors were excluded. As Audubon President T. Gilbert Pearson said, “What good is an eagle anyway?…you cannot eat an eagle; it does not sing…or perform any other special service for man.” By the 1930’s, nesting bald eagles had gone missing in a dozen states and people were waking up to its absence. The decline of America’s winged sovereign implied the loss of something fundamental to the American spirit: a specimen forever safe, tamed, and locked away in a museum, a portrait behind glass.

Bald Eagle champions organized behind their bird as it was being shot out of existence in what habitat remained to it. Eagle fans wrote and distributed pamphlets, articles, and books to raise awareness of the eagle’s plight, while eagle foes raged about all the babies, livestock, and game animals being annihilated by eagles. Titles included Can We Save Our National Bird? and The American Eagle and It’s Alive – Kill It and The Bald Eagle, Our National Emblem: Danger of its extinction by the Alaska Bounty and Misunderstood Eagle, just to name a few. I have to think that outsiders were delighted to see wealthy elites brawling like bar fighters over the fate of America’s national bird.

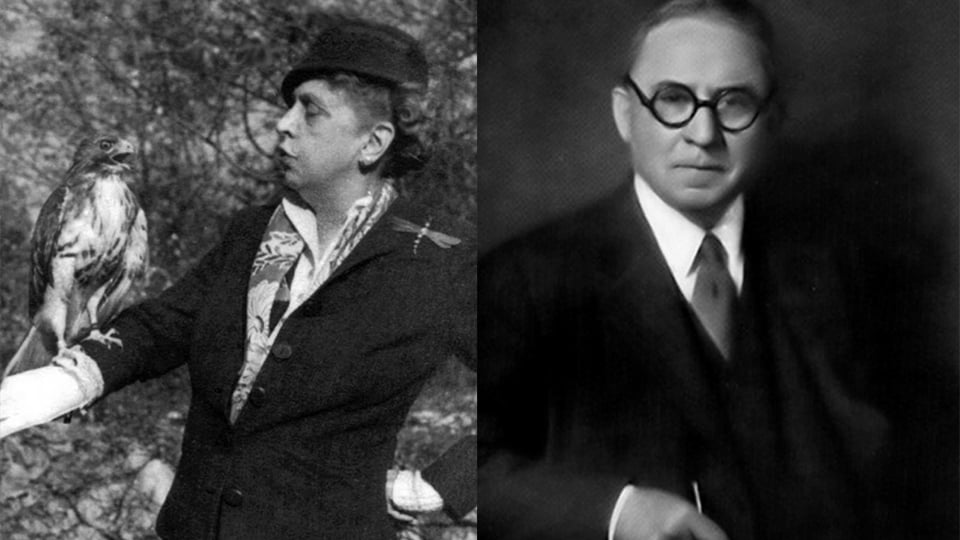

Suffragette Rosalie Edge: Eagle Friend. Audubon President T. Gilbert Peterson: Eagle Foe.

There were a lot of eagle champions, but it took Rosalie Edge, a suffragette, conservationist, activist and the ‘most honest, unselfish, indomitable hellcat in the history of conservation‘, to get the National Audubon Society to recognize the plight of the Bald Eagle at their national convention in 1929. Edge got three bald eagle bills into Congress and Maude Phillips, the president of an animal welfare organization called the Blue Cross Society, finally got one passed in 1940.

Why did Congress finally pass protection for the Bald Eagle? We could not shoot the bird of our nation and have it as a symbol, too – especially in the face of the tide of fascism and Nazism rising in Europe. Symbolism in time of war carried the day and united enough of the nation to get the law passed. And new ideas about conservation led some people to consider eagles as living outside our ideas and values: something living in on its own terms, in its own way. As author Jack E. Davis points out, ‘noble’ and ‘majestic’ are made-up labels, but they are labels that eagles can live with.

The Second Near Extinction

So the Bald Eagle was saved, right? Not so fast! By the late 1940’s, the annual number of Bald Eagle hatchlings began plummeting for unknown reasons. Only 10% of bald eagle travelers at Hawk Mountain in fall of 1957 and 1958 were immature eagles: a drop of 28% from the years recorded before. By the early 1960s, the population had dwindled to 487 pairs of eagles in the lower 48 states. What was going on? A new miracle pesticide called DDT had appeared on the scene! Touted as taking care of everything from agricultural pests to cupboard roaches, the demand for DDT exceeded all other pesticides worldwide. Annual use in the US peaked at about 79 million pounds: almost a half pound for every man, woman, and child in the United States.

At the same time, Americans were becoming concerned about the effects of large-scale pesticide use. Farmers reported sick livestock and dead livestock, a lack of bees, sore throats, headaches, and mouth sores that lasted for months, while DDT was causing massive fish kills in Tampa Bay and other places. As the post-war economy ramped up, some industries were treating the public commons as a personal dumping ground. Rivers caught fire and died, cities choked under blankets of smog, marine life died in massive oil slicks, run-off from sewers dumped excrement into rivers and lakes, communities suffered, and bald eagles (and peregrine falcons) began to disappear again.

Concern about pesticides and pollution went nationwide when a biologist named Rachel Carson wrote a book called ‘Silent Spring’ that helped turn a concerned public into an activist public. The timeline looked like this:

- 1961: Rachel Carson, an American biologist, award-winning writer, and breast cancer survivor, writes Silent Spring

- 1962: President John F. Kennedy awards her the Distinguished Civilian Civil Service Medal

- 1963: The Silent Spring of Rachel Carson airs on national television

- 1963: Congress authorizes the Clean Air Act

- 1964: Rachel Carson dies of cancer at age 58

- 1966: The Endangered Species Act passes

- 1968: Grand Canyon Dams are defeated

- 1969: The Santa Barbara Oil Spill dramatizes the problems of pollution

- 1969: Greenpeace is organized

- 1970: Richard Nixon signs the National Environmental Policy Act

- 1970: The First Earth Day is held

- 1972: DDT is banned in the United States

- 1973: Endangered Species Act passes

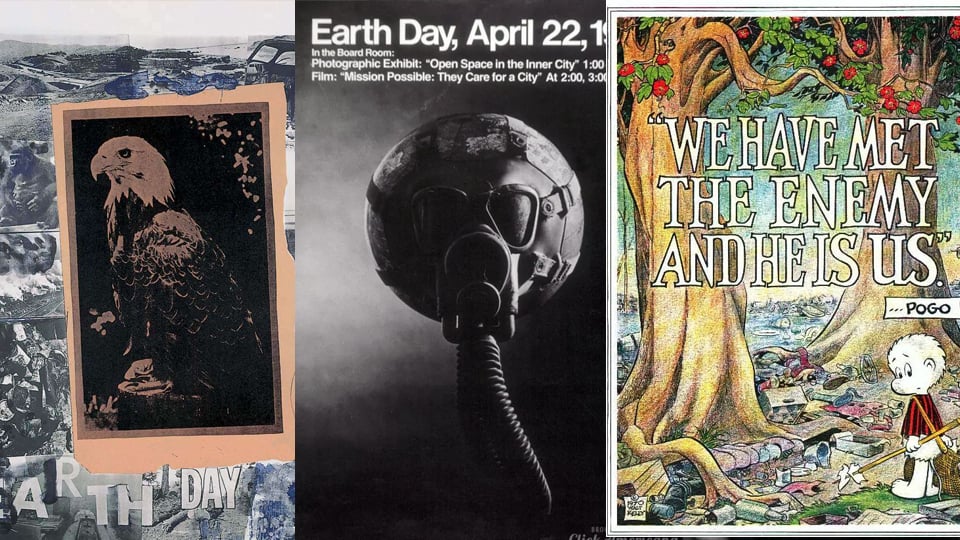

Posters from the first Earth Day. We have a few more over on our Facebook page

As opposition to the conservation movement grew, it was sadly effective to portray conservationists as dilettantes, elites, and out of touch. It’s important to remember that Earth Day grew out of communities who were concerned for the health of their children and the survival of their way of life. They were also tired of rivers catching on fire and smog blanketing the air. Their messages were simple, and they worked: Pollutants are bad for children and other living things. Save endangered species from extinction. Restore our clean air and water. This has to stop!

The Bald Eagle was in serious trouble, but the passage of the Endangered Species and Clean Water Act gave people the tools they needed to create a welcoming and healthy environment. The Federal Government ultimately provided $60 billion dollars to state and local governments to eliminate toxic releases, restore all US waters to a condition safe for drinking, swimming, and fishing by 1983, and end polluted discharge by 1985. At the time, barely one-third of the nation’s waters were swimmable and fishable. While we have a lot more work to do, the number stands at 50% as I write this, and the Bald Eagle and Peregrine Falcon are back with a bang, at levels that are most likely higher than their historic populations.

I’m going to close with a quote from The Bald Eagle: The Improbable Journey of America’s Bird: “The story of the experience of bald eagles as America’s bird is a study in awareness, transformation, and commitment. It is a story that can help us navigate the unprecedented environmental challenges that have arrived decisively in the 21st century, alongside the bald eagles’ comeback.” The Bald Eagle’s recovery twice provided a vision for our future and a blueprint for taking action – an important lesson to take to heart on Earth Day and every other day of the year.

The Raptor Resource Project

The Raptor Resource Project The Raptor Resource Project

The Raptor Resource Project